STRINGS N STEPS - ACADEMY OF PERFORMING ARTS AND FESTIVALS

..........................A Class for the Mass

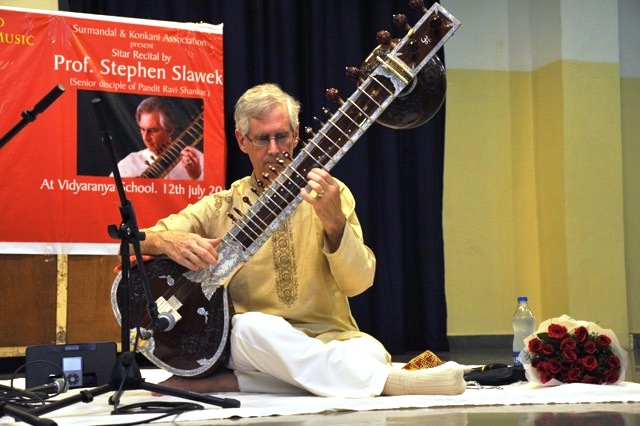

A tête-à-tête With Eminent Maestro, Professor Stephen Slawek.

'Professor Stephen Slawek is an example of a supreme artist who awakens himself with ecstasy in creative manifestation and knowledge, a torch bearer of the tradition of his guru legendary Sitaristlate pandit Ravi Shankar."

~Strings N Steps

Q.Can you put into words your own Personality and Persona?

I don’t like to talk about myself. I think it would be more appropriate for you to say what you think about me from our interaction over the past few years. (That is directed to Sangeeta Majumdar)

Q.You are one of the leading Indian classical musicians now. Did you program things this way?

Well, that might be stretching things a bit. I don’t think of myself as a “leading Indian classical musician.” I have been fortunate to have received taalim from Pandit Ravi Shankar, and I have worked hard to do justice to the effort he put into teaching me. However, the situation in today’s world is such that it is very difficult to find the time and energy that is required to reach 100% of one’s capability. I think of myself as a competent sitarist who is able to transmit my Guruji’s system of improvisation in the raga tradition. I perform primarily to force myself to practice, but I know I could be much better if I had more opportunities, and time, to perform. Of course, I have worked hard to be able to do what I do, but it entailed getting a doctorate in an academic discipline, ethnomusicology, so I have actually been doing double duty in my career as a scholar and a performer.

Q.There are many changes occurring in India. Yes, indeed. Parampara, in Sanskrit, means tradition, which undergoes uninterrupted change. In this context, what do you think, where does Indian Classical music stand?

As with everything, there are promising things, and there are troubling things. Among the promising is access, which is much greater now than in the past. Everything is available on the Internet. This, in itself, of course, also has its drawbacks, but in comparison to just forty years ago, it is much easier for a gifted student to get immersed in the music today, and that will have a positive effect on an individual’s musical development. An interested listener has recordings of concerts from even the 1950s of legendary musicians like Randit Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, and Ustad Vilayat Khan and other great musicians of the time available on YouTube. On the negative side, I think the economic system is making it harder to make a comfortable living as a classical musician. The music has always been such that it can appeal only to those who are willing to make an effort to understand it. Because many in today’s audiences are unable to put in this effort, they want instant gratification. Musicians, especially the younger ones, are responding with stage antics and emphasis on technique and novelty, also engaging in fusion experiments, most of which are like musical trash (my humble opinion). These trends have the potential to change the music in ways that make it more of a popular music genre than a kind of music that has the power to elevate listeners intellectually and spiritually. It will be very sad if the sublime aspect of Hindustani sangita is lost in the future.

Q. How would you describe your music? According to you which part of your rendition makes you different from others. Does your style bear any innovation?

My musical style is that of the Maihar Gharana, especially following in the path that was blazed by Pandit Ravi Shankar. There is still some influence of Dr. Lalmani Misra’s teaching in my tone and style, but I have worked hard to master the sitar technique of Pandit Ravi Shankar. Of course, I am a musical midget in front of his creativity, but I have a lot of company, as even great musicians can be diminished when compared with what he accomplished in his lifetime. As an outsider, I have always felt it was my responsibility to stick to what I had been taught by my guru-s and to uphold the tradition as it was taught to me. When I performed in Agra a few years ago, the students who were in attendance were amazed that I played in a very traditional style. I guess I am out of step with what is going on today!

Q.Will you throw light on your Guru's method of teaching? Is it different from yours? If yes-How? If no-why?

Guruji was very precise in all of his teaching. When introducing a raga, he would usually give one or two ascending-descending phrases. Remarkably, he had a knack for balancing these rhythmically so they could be played in different layakaris. For example, in Tilak Kamod (starting on mandra PA and moving up, then back down), this fits nicely into rupak tala, has phrases that cross the beat, giving some practice to rhythmic stability, but also perfectly encapsulates the calan of Tilak Kamod:

P - N - S – R – G, S – R – M – P – D -, M – P – N – S – R – G – S – R – N – S – P – D – M – G – R – G – S – N.

After getting the basic arohavaroha somewhat ingrained, he would move on to demonstrating finer details of the raga, sometimes by playing alap phrases that were to be repeated exactly as he played them, and then moving into some jor phrases. He would then move to gats, usually starting with a slow gat. Sometimes he would compose fixed tans and tihais in the gats, other times he would improvise phrases, giving the students opportunities to copy the phrases. This would go on until he would bring the idea to a final conclusion, often with a tihai to mukhra. Then he would be off improvising again. In this way, there was a sliding scale of teaching fixed tans and todas, usually at the earlier stages of learning, and then teaching phrases that could be taken by a student and used as a basis for improvisation. Sometimes he would use table bol-s to create a rhythmic structure for a tihai that could serve as the basis for any number of different tihais by changing the notes, but keeping the same rhythm. He would teach for many hours at a sitting. He was very generous as a guru, giving so much music education that it was like a gushing fountain of musical ideas. We poor students had to try to drink up as much of the flood as we could!

In principle, I try to teach in the same manner as Guruji taught me. Of course, I have to adjust what I teach to the capability of the student. Also, I am not as fast in devising new ideas in creating tan-s and tihai-s, so I don’t overwhelm my students with a flood of ideas. I often get frustrated in my institutional teaching because so many beginners want to learn, but they have so little ability, and I’m stuck teaching basic exercises and simple gats. It is really an impediment to my own thinking and creativity. Luckily, I have one very promising student now who picks up very quickly and has made great progress. I will do my best to make her an outstanding performer. She has been studying for three years now and is ready for more advanced things.

Q. Do you think that there are separate methods or techniques in dance for man and woman?

I am totally ignorant of dance. It is one of my weak points. I would expect that the physical forms of men and women would demand different techniques of movement. It would seem logical.

Q. Does your heart still miss a beat before concerts after so many years of experience?

Not just one beat, but many! I have always been nervous before performances. I never feel good about my concerts, as I always feel I end up going in directions that were unintended, but that is an aspect that is built into improvisational music. The first meend in alap is always crucial for me. If I shake from nervousness, or my hand feels floppy and the notes come out weak or go out of tune, that is so disastrous! But it happens sometimes, and you just have to suck it up and be brave to go on. I confess that I do enjoy getting appreciation from a large audience, and it does inspire me to play to the best of my abilities.

Q. How do you rate your success?

B+. Actually, I have been very lucky to be able to do what I do. My first sitar teacher, Dr. Lalmani Misra, was an excellent teacher. His training took me to a stage of accomplishment that impressed Ravi Shankar and caused him to be willing to take me on as a student. It was all very proper, though, as he insisted that I send a telegram to Dr. Misra requesting permission to learn with him (this was in 1977, many years before e-mail!). Dr. Misra gave me his blessings and wished me success. Guruji arranged a ganda ceremony that took place at a temple associated with the Ramakrishna Mission in Los Angeles. It was a special event in my life. If everything had stopped at that point, I would have considered my success complete, as I had a goal to study with Ravi Shankar. That he became my guru for over thirty years of training (of course, not continuous, but many periods of intense work!) is something I will always cherish and be thankful for. It was very difficult for me when I first started with him, as he changed my technique completely—for both the right and left hands. I felt like a beginner even though I had been playing for seven years and had already given many concerts in India, even on All India Radio!

Q. There is a popular opinion that the Younger generation isn't much interested in classical music- dance forms. Do you agree? How would you justify your opinion?

I would have to spend more time in India to be able to give an informed answer to that question. As I said earlier, sastriya sangita is a kind of music that requires the listener to expend some effort in order to understand what is happening in the music. There is no doubt that in today’s world, people are more concerned with fast gratification without the need to make an effort. It makes it difficult for classical musicians to compete in the market place. That is why some additional support systems are necessary to preserve the tradition. I am very impressed with the work of the ITC Sangeet Research Academy in Kolkata.

Q. Can you share your most memorable onstage moment?

It is hard to think of one moment. There have been a few that were memorable because things didn’t go well and some where everything worked and the audience response was almost like thunder. I had one concert with Anindo Chatterjee on tabla that went very well. Also one with Sukhvinder Singh Namdhari. Both are such excellent masters of the tabla that it was like riding wild horses while they were accompanying, but I managed to keep everything together.

Q. What is your favourite Idea of Holidaying? Do you think it is necessary to have leisure-voids while working?

I have so few opportunities to take a holiday that I can’t really say. My experience is that a holiday from practice means going backwards in making progress. I am in a period where I had a lot of work to do on my house and yard for the past two months and my practice has been minimal. It wasn’t a holiday, as I did a lot of heavy lifting, repairs of sheet rock, painting, and so forth. We call it sweat equity. Anyway, I have begun the process of increasing time devoted to practice and it is very painful not being able to play like I was playing just a few months ago. It will now take me at least six weeks to get back into playing shape. So it goes with the multiple responsibilities I must meet.

Q. If you were given the chance to live again, how would you want it to be?

I would want to come back as Jon Snow in Game of Thrones. That way, I could die and come back even one more time.

Stephen Slawek is Professor of Music (Musicology/Ethnomusicology) and core faculty affiliate of the South Asia Institute at The University of Texas at Austin. He teaches academic courses in ethnomusicology, with a concentration on the musical traditions of South Asia, as well as the performance practice of the sitar and tabla. He was instrumental in acquiring the Butler School’s Javanese gamelan, and has been directing that ensemble for the past four years. As a sitar disciple of the late Pandit Ravi Shankar, he has performed on that instrument extensively in India, Europe and the United States, sharing the stage with such notable musicians as Zakir Hussain, Swapan Chaudhuri, Sukhvinder Singh Namdhari, Kumar Bose, and with the late maestro himself, Pandit Ravi Shankar. He has authored publications on various aspects of the musical culture of India and, since 1977, has presented papers at scholarly conferences here and in Europe and India. He has served on the Council and the Board of Directors of the Society for Ethnomusicology, is a former editor of Asian Music, the Journal of the Society for Asian, has served as Chair of the Ethnomusicology Committee of the American Institute of Indian Studies.

|

Registered under Society Act XXI of 1860 Regn. No S-E/32/Distt. South East-2013 |

|